Hacking into computers is illegal pretty much worldwide.

In the UK, the key legislation that deals with computer crimes is the Computer Misuse Act 1990, which has formed the basis of much of the computer crimes legislation in many of the Commonwealth nations.

But it's also a deeply controversial piece of legislation, and one that has recently been updated to give GCHQ, the UK's primary intelligence organization, the legal right to hack into any computer they so desire. So, what is it, and what does it say?

The First Hackers

The Computer Misuse Act was first written and put into law in 1990, but that's not to say that there was no computer crime prior to then. Rather, it was just incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to prosecute. One of the first computer crimes to be prosecuted in the UK was R v Robert Schifreen and Stephen Gold, in 1985.

Schifreen and Gold, using simple, off-the-shelf computer equipment, managed to compromise the Viewdata system, which was a rudimentary, centralized precursor to the modern Internet owned by Prestel, a subsidiary of British Telecom. The hack was a relatively simple one. They found a British Telecom engineer, and shoulder-surfed as he keyed in his login credentials (username '22222222' and password '1234'). With this information, they ran amok through Viewdata, even browsing the private messages of the British Royal Family.

British Telecom soon became suspicious and started to monitor the suspect Viewdata accounts.

It wasn't long until their suspicions were confirmed. BT notified the police. Schifreen and Gold were arrested and charged under the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act. They were convicted, and fined £750 and £600 respectively. The problem was, the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act didn't really apply to computer crimes, especially ones that were motivated by curiosity and inquiry, not financial goals.

Schifreen and Gold appealed against their conviction, and won.

The prosecution appealed against their acquittal to the House of Lords, and lost. One of the judges in that appeal, Lord David Brennan, upheld their acquittal, adding that if the government wished to prosecute computer criminals, they should create the appropriate laws to do so.

This necessity lead to the creation of the Computer Misuse Act.

The Three Crimes Of The Computer Misuse Act

The Computer Misuse Act when introduced in 1990 criminalized three particular behaviors, each with varying penalties.

- Accessing a computer system without authorization.

- Accessing a computer system in order to commit or facilitate further offenses.

- Accessing a computer system in order to impair the operation of any program, or to modify any data that doesn't belong to you.

Crucially, for something to be a criminal offense under the Computer Misuse Act 1990, there has to be intent. It's not a crime, for instance, for someone to inadvertently and serendipitously connect to a server or network they don't have permission to access.

But it's entirely illegal for someone to access a system with intent, with the knowledge that they don't have permission to access it.

With a basic understanding of what was required, mainly due to the technology being relatively new, the legislation in its most fundamental form didn't criminalize other undesirable things one can do with a computer. Consequently, it has been revised multiple times since then, where it has been refined and expanded.

What About DDoS Attacks?

Perceptive readers will have noticed that under the law as described above, DDoS attacks aren't illegal, despite the vast amount of damage and disruption they can cause. That's because DDoS attacks don't gain access to a system. Rather, they overwhelm it by directing massive volumes of traffic at a given system, until it can no longer cope.

DDoS attacks were criminalized in 2006, one year after a court acquitted a teenager who had flooded his employer with over 5 million emails. The new legislation was introduced in the Police and Justice Act 2006, which added a new amendment to the Computer Misuse Act that criminalized anything that could impair the operation or access of any computer or program.

Like the 1990 act, this was only a crime if there was the requisite intent and knowledge. Intentionally launching a DDoS program is illegal, but becoming infected with a virus that launches a DDoS attack is not.

Crucially, at this point, the Computer Misuse Act wasn't discriminating. It was just as illegal for a police officer or spy to hack into a computer, as it was for a teenager in his bedroom to do it. This was changed in a 2015 amendment.

You Can't Make A Virus, Either.

Another section (Section 37), added later on in the life of the Computer Misuse Act, criminalizes the production, obtaining and supply of articles that could facilitate a computer crime.

This makes it illegal, for instance, to build a software system that could launch a DDoS attack, or to create a virus or trojan.

But this introduces a number of potential problems. Firstly, what does this mean for the legitimate security research industry, which has produced hacking tools and exploits with an aim to increase computer security?

Secondly, what does that mean for 'dual use' technologies, which can be used for both legitimate and illegitimate tasks. A great example of this would be Google Chrome, which can be used for browsing the Internet, but also launching SQL Injection attacks.

The answer is, once again, intent. In the UK, prosecutions are brought by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), which determines whether someone should be prosecuted. The decision to take someone to court is based upon a number of written guidelines, which the CPS have to obey.

In this instance, the guidelines state that the decision to prosecute someone under Section 37 should only be done if there is criminal intent. It also adds that in order to determine if a product was built in order to facilitate a computer crime, the prosecutor should take into account legitimate usage, and the motivations behind building it.

This, effectively, criminalizes malware production, whilst allowing the UK to have a flourishing information security industry.

"007 - License to Hack"

The Computer Misuse Act was again updated in early 2015, albeit quietly, and without much fanfare. Two important changes were made.

The first was that certain computer crimes in the UK are now punishable with a life sentence. These would be given out if the hacker had intent and knowledge their action was unauthorized, and had the potential to cause "serious damage" to "human welfare and national security" or were "reckless as to whether such harm was caused".

These sentences don't appear to apply to your garden variety disaffected teenager. Rather, they're saved for those who launch attacks that have the potential to cause serious harm to human life, or are aimed at critical national infrastructure.

The second change that was made gave police and intelligence operatives immunity from existing computer crime legislation. Some applauded the fact that it could simplify investigations into the types of criminals who could obfuscate their activities through technological means. Although others, namely Privacy International, were concerned that it was ripe for abuse, and the sufficient checks and balances aren't in place for this type of legislation to exist.

Changes to the Computer Misuse Act were passed on March 3rd 2015, and became law on May 3rd, 2015.

The Future of the Computer Misuse Act

The Computer Misuse Act is very much a living piece of legislation. It is one that has changed throughout its life, and will likely continue to do so.

The next likely change is due to come as a result of the News of The World phone hacking scandal, and will likely define smartphones as computers (which they are), and introduce the crime of releasing information with intent.

Until then, I want to hear your thoughts. Do you think the law goes too far? Not far enough? Tell me, and we'll chat below.

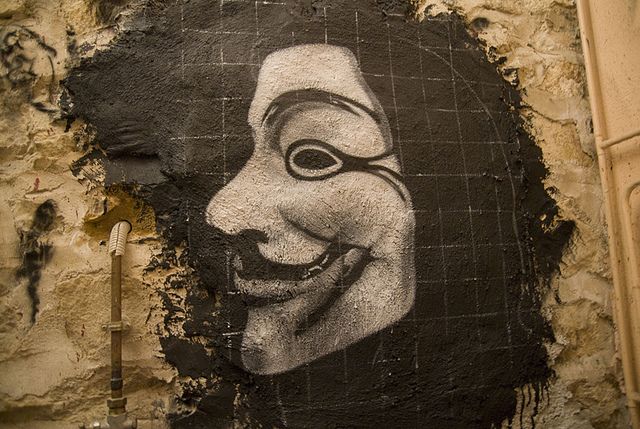

Photo credits: hacker and laptop Via Shutterstock, Brendan Howard / Shutterstock.com, Anonymous DDC_1233 / Thierry Ehrmann, GCHQ Building / MOD